The Contemporary Chinese Art market is diverse and vibrant. Chinese artists are working continuously to challenge and reinvent the cultural heritage accumulated over the past several thousand years. This could not have happened without the rapid socio-economic changes of the recent half century.

Hua is a leading participant and promoter of this rich field of artistic talent. We want to help people who are interested to understand more about Contemporary Chinese Art.

This is the first part of a 4-part series that aims to provide an introduction to the history of Contemporary Chinese Art.

The Beginning

In December 1978, Deng Xiaoping announced his Open Door Policy that would forever change the Chinese economy. More importantly, it was also the moment that marked the beginning of Contemporary Chinese Art history. As foreign businesses were welcomed into China, foreign ideas were introduced into Chinese society along with them. Among these ideas are the western modernist philosophy and aesthetics. Translations of works by thinkers like Foucault flourished among the younger people. As a result, they influenced and encouraged a new generation of Chinese artists who wished to steer away from the state-mandated Socialist Realism style art during the Cultural Revolution period.

One crucial event that testified to such change of direction is the Stars Art Exhibition, whose participants are later known as the Stars Group. Its members include Qu Lei Lei, Wang Keping, Ma Desheng, Huang Rui, Li Shuang, among others. The exhibition opened on 27 September 1979 outside the National Art Museum of China in Beijing after being denied an official exhibiting space. Most of the participating artists were self-taught with no Academy training, nonetheless, the exhibition drew great attention from all sectors of society and was visited by a large number of people.

Wang Keping, Silence, 1978

Wang Keping’s shocking wood sculpture embodies the critical spirit of the Stars Group artists. Eye blinded, mouth stuffed, the suffering face is a protest and an emotional representation of the condition of a society without total freedom. The medium of this work is also worth noting, as most artworks during this period were in the format of ink or oil painting. Silence is significant both in terms of its expressive quality and its cultural value.

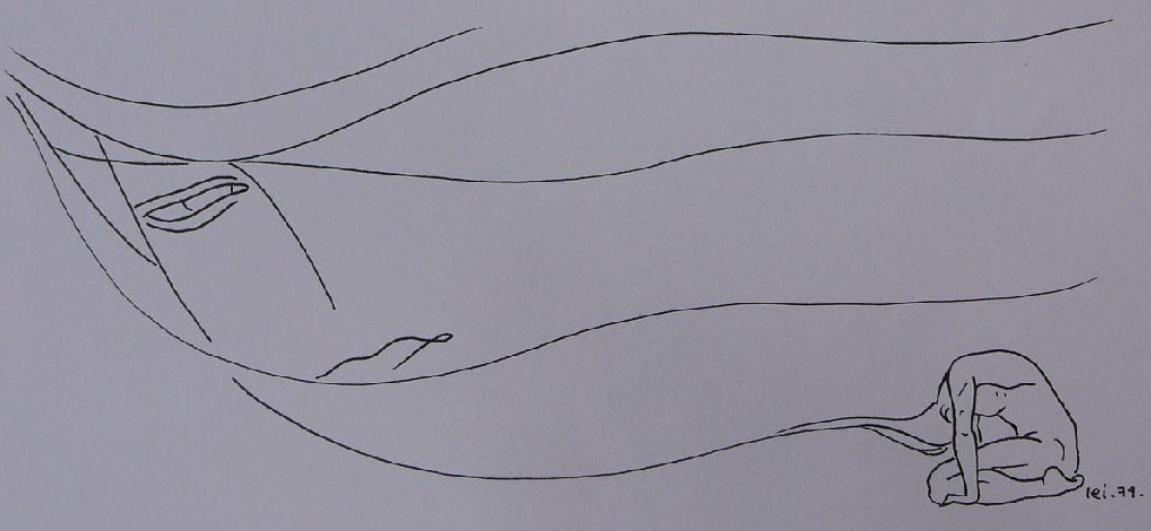

Qu Lei Lei, Wind, 1979

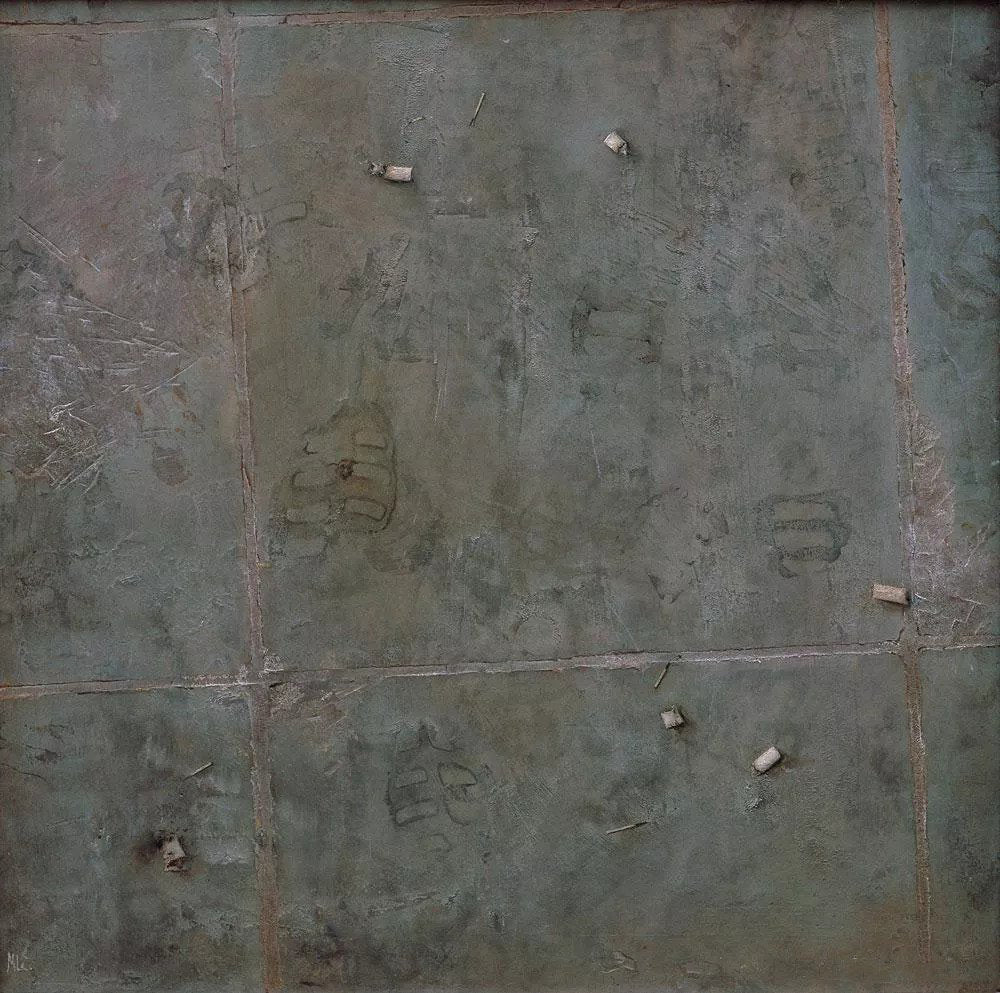

Mao Lizi, Wander (徘徊)

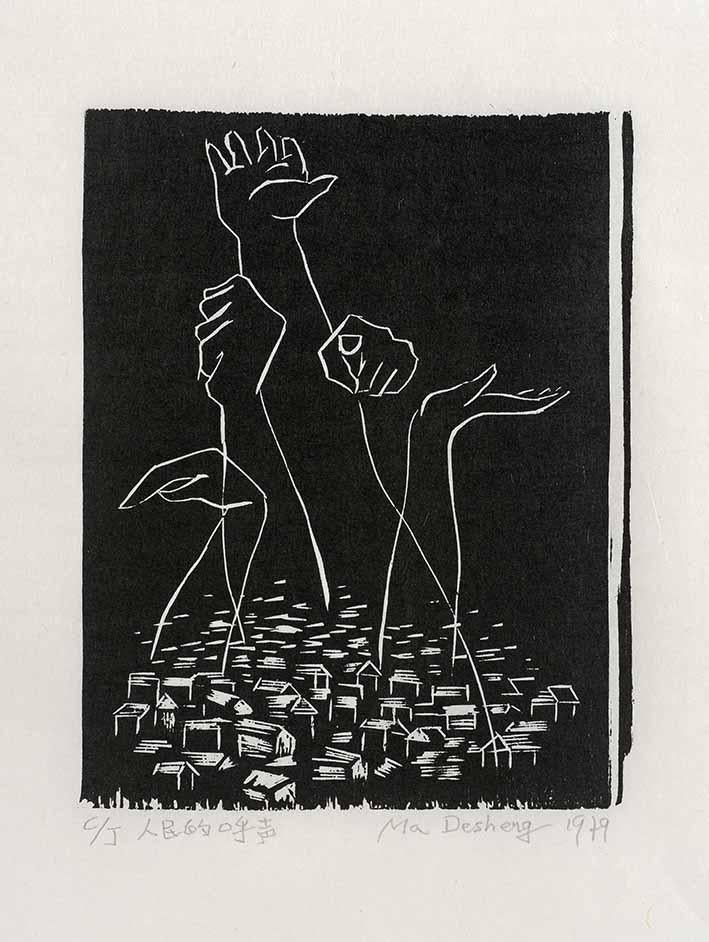

Ma Desheng, The People’s Cry, 1979

Continuing the legacy of the Stars Art, in the mid 1980s China had a relatively free socio-political climate, which allowed for the emergence of 85’ New Wave, an avant-garde movement that explored and expanded the scopes and ways of expression in art. The main theme of 85’ New Wave is the emancipation of humanity, specifically emphasising the consciousness of personality and free expression of spirit. Artists realised that there was a gap between the old and new system of ideas, and it was their duty to enlighten the society.

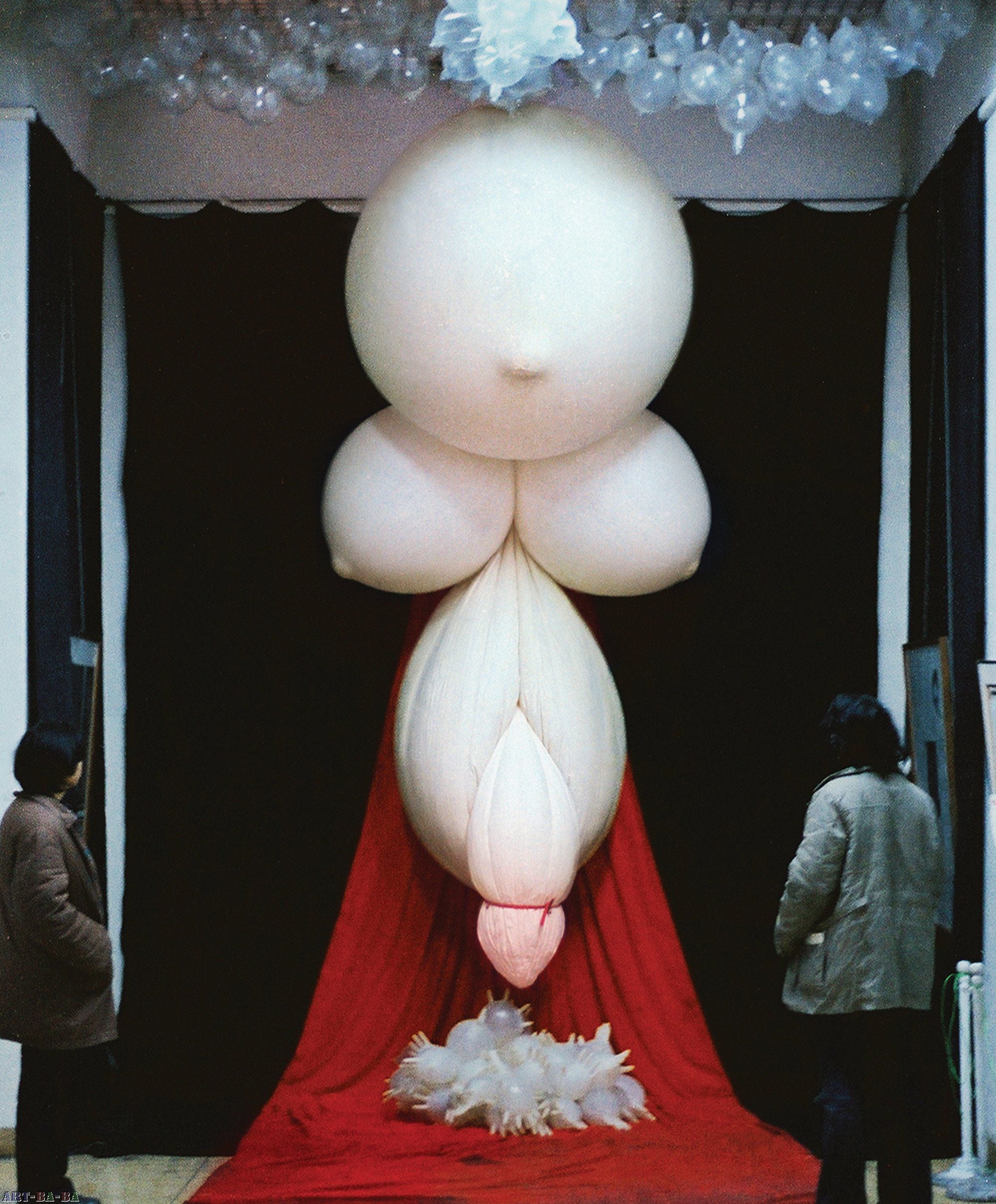

Some of the exemplary artists of this period include Ai Weiwei, Xu Bing, Huang Yong Ping, The Gao Brothers etc. The movement culminated in the China/Avant-Garde Exhibition in 1989. The show opened on 5 February inside the National Art Museum of China, encompassing works from all the most experimental and avant-garde artists across China, many of whom were performance artists. The poster for the exhibition features a “No U-Turn” sign, speaking metaphorically to the forward-looking attitudes shared by all participants.

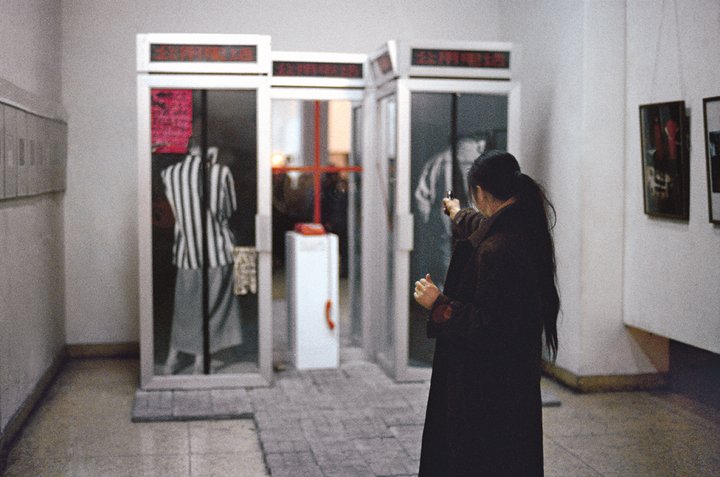

However, the show was shut down after only a couple hours when artist Xiao Lu shot her own work Dialogue with a gun. Unlike the Stars Art exhibition a decade earlier, China/Avant-Garde did not expand and challenge further the existing social order, rather, it witnessed the ending of an era and foretold a major change that was about to happen to the Chinese society. Only four months after the exhibition, on 4 June 1989, Tanks paraded into the Tiananmen Square.

Xu Bing, A Book from the Sky, 1988

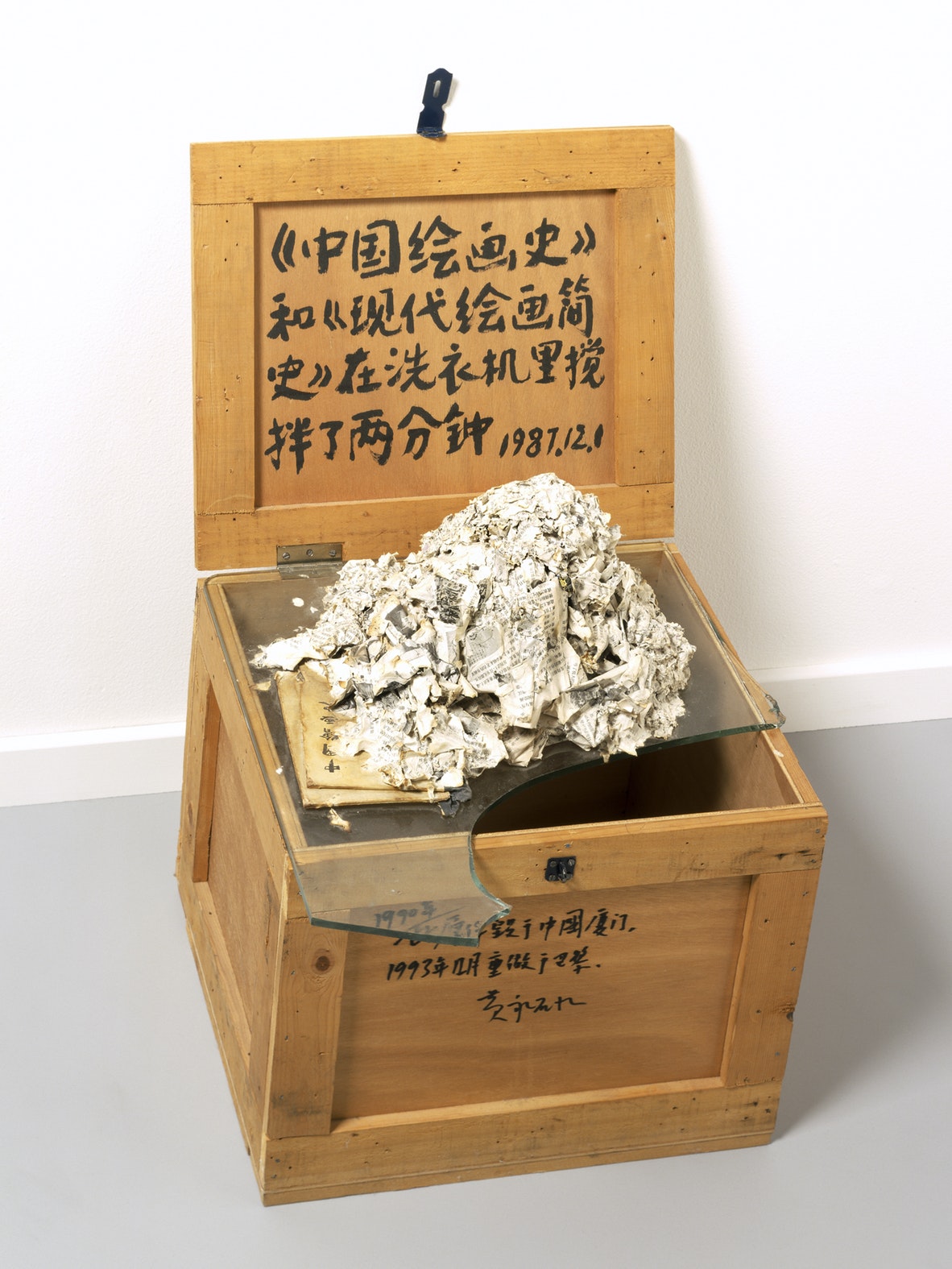

Huang Yong Ping, The History of Chinese Painting and the History of Modern Western Art Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes, 1987

Like the title describes, Huang Yong Ping literally blends two art history books - Wang Bomin’s History of Chinese Painting and Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting – together by putting them through a washing machine. The resulting pile of paper scraps is exhibited on top of a wooden box in a matter-of-fact way. The candid and plain description of the process and its result contrast dramatically with the metaphorical significance of the action that one may infer from its material residue. The illegibility of resulting text proves that the interaction between two cultures does not happen in a rigid, methodological fashion; rather, each culture is overlapped and infused with the other through constant motion. Huang’s work expresses an iconoclastic and anti-institutional sentiment, which is the essence of the Xiamen Dada Group.

Xiao Lu, Dialogue, 1989 – the moment she shot the gun

Zhang Xiaogang, Bloodline: Big Family 9, 1996

The Gao Brothers, Midnight Mass, 1989

The period between 1979 and 1989 was absolutely crucial for the development of Contemporary Chinese Art because it collided with some of the pivotal moments of modernisation in China. The influx of new ideas and relaxation of political climate gave birth to a critical and organic art scene that expressed the possibilities of the future. New generations of artists like The Stars Group and the 85’ New Wave defied the official rules and created their own. However, all the positive energy would come to an abrupt stop in June 1989 when a turn in direction was about to happen.

Article by Ariana Guo

Learn more about some of the artists’ more recent works: